Thoughts on traditional folk tales in a modern world

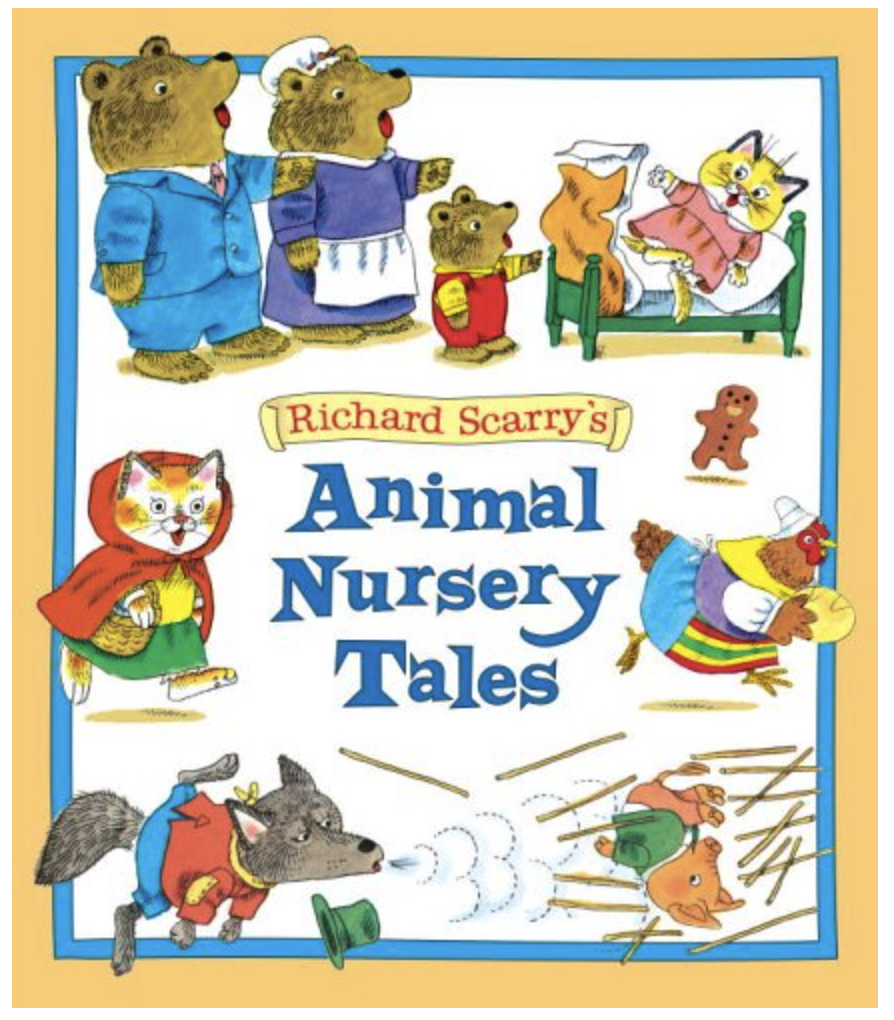

Last week, I brought Richard Scarry’s Animal Nursery Tales over to my sister’s house to read to my three (soon to be four) year old nephew. I’d found the book at an estate sale a few months ago. It had all the classic children’s stories — Little Red Riding Hood, The Three Little Pigs, Goldilocks and the Three Bears to name a few — but with Scarry’s classic and enchanting style of illustration. What a find!

The front and back cover serve as a sort of pictorial table of contents. Owen and I looked through the pictures together and we settled on our first story, Little Red Riding Hood. “Have you heard this story before?” I looked at him and then over at his mother, who was playing with Owen’s baby brother on the other sofa. She shook her head. Wow, I thought. What a first. Imagine never having heard Little Red Riding Hood before. I couldn’t.

And so we began the story. He was very engaged. I thought to myself, reading through the first few pages, this flows so well. Lots of repetition and interesting visuals — no wonder it’s a classic. I did my best Wolf voice as he asks Little Red Riding Hood, “Where are you going, little miss?” upon meeting her in the forest. I made big eyes at Owen and he was hooked, wondering what the big bad wolf was going to do next. I read how the wolf hurried over to Grandmother’s house, getting there before Little Red Riding Hood.

I did my best Grandmother voice as she calls out, “Who is there?” when the wolf knocks at the door before switching quickly to a strange wolf-pretending-to-be-a-little-girl voice as he replies, “It is I, Little Red Riding Hood.” Checking to make sure Owen was following, I asked him, “But is it really Little Red Riding Hood?” “No!” He was actually paying attention and following along! I’d had trouble lately finding books that sustained his interest. This was great!

And then we got to…

“Just pull the latch string and come in, my dear!” said Grandmother.

The wolf came in.

He leaped at Grandmother and swallowed her whole!

I had forgotten this part was here. I looked over at Owen. He seemed okay… We continued the story. But I was on high alert now and realizing with each new page, This is actually a terrifying story. Grandmother has been eaten. Now the wolf is impersonating Grandmother. Poor Little Red Riding Hood has unknowingly come right up to the wolf. She doesn’t know it’s the wolf, but we do, and the build up of ‘What big ears you have’ and ‘What big eyes you have’ leading up to the climax of ‘What big teeth you have’ is very, very scary. The story wraps up with the wolf chasing Little Red Riding Hood out of the house and then a woodcutter cutting open the wolf to rescue Grandmother from his stomach. Grandmother and Little Red Riding Hood live and are not physically harmed, but one can imagine that they (and perhaps even a young reader!) are emotionally traumatized.

We’d gotten to the end of the story. I was a little worried about Owen and ready to call it a day, but he wanted another story. Maybe that wasn’t so bad after all? We looked through the front and back cover again. I suggested The Three Little Pigs. Owen looked at me cautiously. “Is there a wolf in it?” he asked. “Yes…” “Is the wolf bad?” “Yes…” “Then I don’t want to read that one.” I winced. Poor little guy.

So we read The Gingerbread Man. In this story, a gingerbread man comes to life and runs away. He outruns everyone in the town and they’re all chasing him. When he gets to a river and realizes he can’t get across, a fox offers him a ride across on the fox’s back. The gingerbread man accepts. Partway across the river, the fox tells the gingerbread man that the water is getting higher and he had better climb up onto his head. So the gingerbread man does. Then, the fox says the water is getting even higher and the gingerbread man should climb up onto the fox’s nose. So he does. And then the fox eats the gingerbread man and the story ends. “That’s it?” Owen asked. Yes, Owen, that’s it. Both feeling a little flat at that point, we put the book to rest.

Later that night and all through the next day, I wondered about what I had read. Those were the stories of my childhood, told to me a million times over in different books and TV shows. I turned out fine. Everybody has read them. We’re all fine. Maybe we’re too soft now is all. They’re stories.

But that didn’t feel satisfying and so I thought some more.

I came to what I thought was a helpful question, What is the purpose of children’s stories?

Surely, children’s stories are meant to entertain. But then, they’re also often instructive.

And what we’ve wanted stories to teach children has changed over time. Little Red Riding Hood is thought to have originated in the 17th century. According to Hannah Newton, author of The Sick Child in Early Modern England, 1580–1720, in 17th century England, almost one-third of young people died before they were 15 years old. And ‘Rather than shielding their offspring from these foreboding facts, parents encouraged their children to think about their own mortality.’ (source) Indeed, in tale after tale, death or the possibility of death makes a recurring appearance. Little Red Riding Hood is an instructive tale that warns about threats to one’s own mortality. Do not talk to strangers — or you may die. Beware of wolves — or you may die. Similarly, with The Gingerbread Man. Do not unthinkingly place your trust in strangers, even if they appear to be trying to help you — or you may die. Death was a significant and real threat, so many of these stories provided instruction as to how to avoid death.

Thankfully, in most parts of the world, death in childhood is much less of a threat. And so it makes sense that newer stories don’t provide this flavor of instruction. Simple survival is no longer the primary concern for most parents.

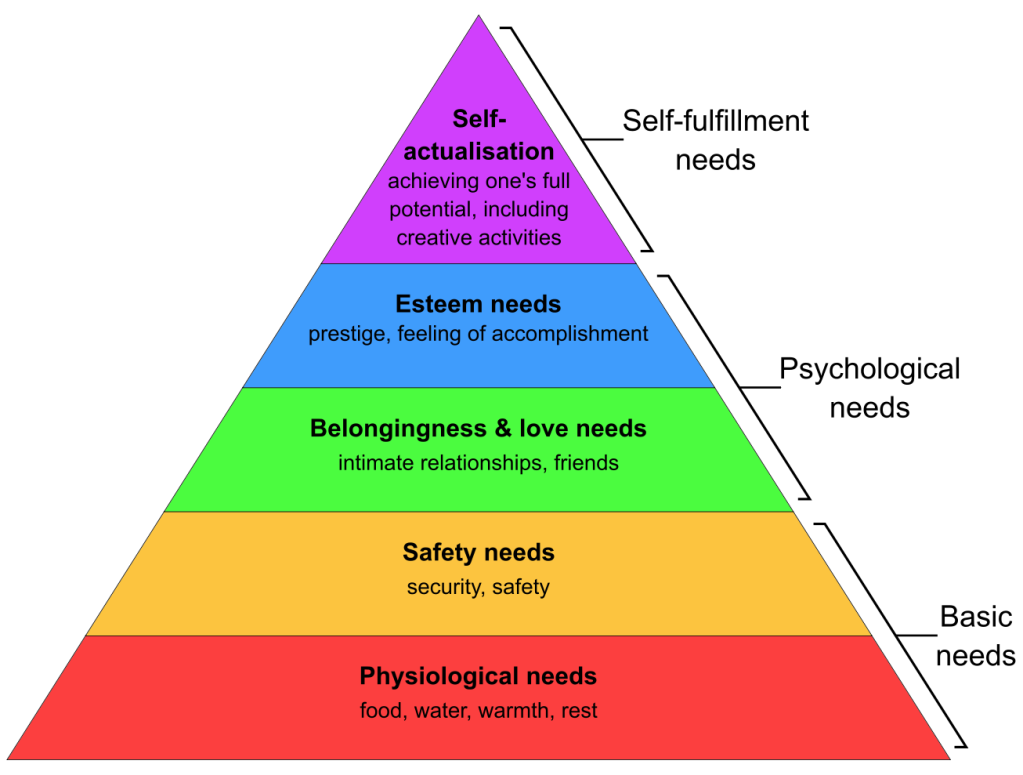

We can refer to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs for clues on what instead may be a new focus. According to Maslow, once physiological needs (food, water, warmth, rest) and safety needs (security and safety) — together what I am calling simple survival — are met, then the next needs are ‘Love and Belonging’ (intimate relationships, friends, family, connection) and after that ‘Esteem’ (respect, self-esteem, confidence). When I think of modern children’s stories, they absolutely seem to be focused on these next two categories of needs. Modern stories do not tend to instruct children on how to physically survive, but instead instruct on how to form and maintain relationships and how to develop a sense of self-worth.

Think of the recent Disney movie, Encanto. Mirabel, the only one in her family who has not been given a magical gift, struggles to feel like she fits in with her family. As she tries to help the family, initially it seems like she’s making things worse and so she questions her own abilities and worth. By the end of the story, by being herself and by being honest and open with her family, she is able to save the family and realize her own place in the family as well as develop feelings of self-worth and confidence.

Think of the classic Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, which provided instruction on how to handle emotions such as anger, and also on how to process complicated but realistic threats to a child such as divorce or the death of a loved one.

These are the problems of today’s children, and we have updated our stories to reflect that.

Naturally, some of the older children’s tales now feel a little out of place.

And so while my initial response to reading Little Red Riding Hood was Well, I read that as a kid. We’re too soft now, my thoughts have evolved. I now think that just because it’s a story that’s familiar doesn’t mean that it will have more value to a child. A good story for a child has some combination of entertainment and instruction. Little Red Riding Hood no longer instructs, but it absolutely still entertains, provided that any fear the child feels does not overshadow any entertainment value he may receive. And this last part depends on the child and their age and maturity level.

Was Little Red Riding Hood a good story for Owen? Eh…I don’t think it did a terrible amount of harm, but he probably wasn’t quite ready for it. I told him a story that had a lesson he didn’t really need and that was probably equally scary as it was entertaining. There are lots of stories out there that provide lessons that are more useful to him that he would find just as entertaining (and less scary). I’ll probably stick with those for now.

A friend once told me that to her, being kind was an ongoing journey and one that took practice. Just as with anything else – like becoming good at playing an instrument – becoming good at being kind took hard work. At the time, I hadn’t known what she’d meant. Now, I think I’m beginning to understand.

A friend once told me that to her, being kind was an ongoing journey and one that took practice. Just as with anything else – like becoming good at playing an instrument – becoming good at being kind took hard work. At the time, I hadn’t known what she’d meant. Now, I think I’m beginning to understand.

It is a different story unfortunately for shorter works – short stories and creative nonfiction articles specifically (hereon, for simplicity’s sake, both are referred to as ‘short stories’). I have yet to find a resource out there that makes it easy – or forget easy, possible, to comb through the content out there to find pieces that will speak to you.

It is a different story unfortunately for shorter works – short stories and creative nonfiction articles specifically (hereon, for simplicity’s sake, both are referred to as ‘short stories’). I have yet to find a resource out there that makes it easy – or forget easy, possible, to comb through the content out there to find pieces that will speak to you.